Like most reporters in Hawaii, in the hour or so after Alexander & Baldwin’s Jan. 6 announcement that they would shut down their Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar (HC&S) mill in Pu‘unene by the end of this year, I watched with growing fascination as my email inbox quickly filled with statements from public officials wanting to weigh in. Reading through them, I kept seeing the word “sad.”

U.S. Senator Brian Schatz said the news “deeply saddened” him. Hawaii House Speaker Joe Souki called it “a sad day indeed.” Governor David Ige said he received the news “with sadness.” State House member Justin Woodson (who represents Central Maui, where many cane workers live) said he was “saddened” by how the decision would affect the mill’s nearly 700 employees.

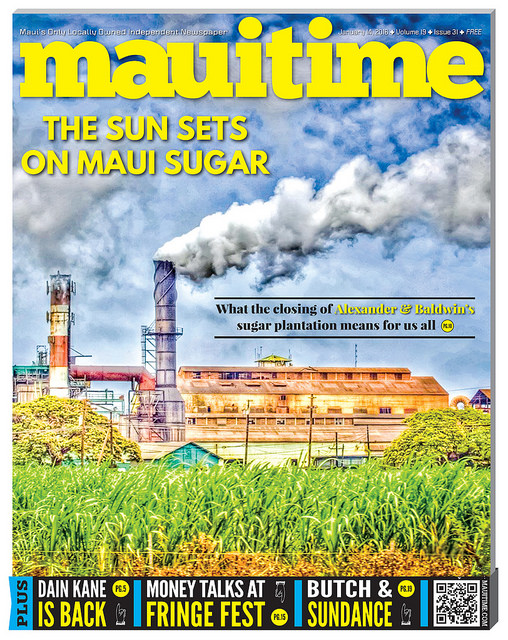

HC&S has grown, harvested and processed sugar cane into molasses on Maui since 1870. Their 36,000-acre sugar plantation is the last such operation in Hawaii, but it’s fallen on hard times; has for some years now. A few months ago, HC&S also lost a potentially big power-sharing deal with Maui Electric Co. that would have given it about $19 million in revenue, theHonolulu Star-Advertiser reported on Jan. 10. But in their own official statement on the mill closure, A&B officials blamed it all on agribusiness losses.

“A&B’s roots literally began with the planting of sugar cane on 570 acres in Makawao, Maui, 145 years ago,” A&B Executive Chairman Stanley M. Kuriyama, said in his company’s Jan. 6 announcement. “Much of the state’s population would not be in Hawaii today, myself included, if our grandparents or great-grandparents had not had the opportunity to work on the sugar plantations. A&B has demonstrated incredible support for HC&S over these many years, keeping our operation running for 16 years after the last sugar company on Maui closed its doors. We have made every effort to avoid having to take this action. However, the roughly $30 million Agribusiness operating loss we expect to incur in 2015, and the forecast for continued significant losses, clearly are not sustainable, and we must now move forward with a new concept for our lands that allows us to keep them in productive agricultural use.”

The news seemed to surprise many. Lieutenant Governor Shan Tsutsui found the announcement “hard to believe.” “Personally, I was shocked,” ILWU President Donna Domingotold KHON 2 news.

Others, like anthropologist Carol MacLennan, who has written extensively about Hawaii’s sugar industry, had a different reaction. “I wasn’t surprised,” MacLennan told me. “I knew it was coming. They’ve been hinting at it.”

Indeed, though The Maui News consistently buried the most dire revelations in their accounts, they did report over the last year or two that A&B was moving away from sugar, perhaps soon rather than later:

• Aug. 11, 2014: A second quarter report shows that A&B’s agribusiness posted a profit of just $400,000–down from $8.3 million in the same quarter the previous year. Sugar production as a whole is down, blamed on wet weather.

• Nov. 6, 2015: “Significant” third quarter losses for HC&S show a $9 million operating loss for the July-September quarter. Sugar production comes in at 42,500 tons, down from 67,000 tons during the same period of 2014. What’s more, company officials say that they’re looking at “diversifying the crop grown on its 36,000 acres” and will make an announcement on the future of the plantation “by its next earnings call,” which would take place no later than early March 2016.

• Dec. 4, 2015: HC&S announces that it is conducting a grass-fed beef experiment on 29 of its acres over by old Maui High with 15 head of cattle. One A&B official tells the paper that since November, the company has been seeking an “alternative business model,” and is trying out various other ag plans.

Then on Jan. 4 of this year, Insider Trading Report noted that A&B stock had fallen rather sharply: “2.16% during the past week and dropped 7.2% in the last 4 weeks.” Forty-eight hours later, A&B officials announced that they were ditching sugar entirely.

The mill had simply become unprofitable. It’s why all the other mills in Hawaii closed, too. Wet weather hurt, but sugar crop yields have been falling in Hawaii for decades. The question was never if the Pu‘unene mill would close, but when.

As a result of this decision, most of the 675 or so people who work in the Pu‘unene mill will lose their jobs. If the last 45 years of mill closures in Hawaii are any guides, the transition won’t be easy–there just isn’t enough ag around to pick up the slack, leaving many workers with no other option than to try to move over to the service industry. This, as would be true for any news of mass layoffs, is undeniably sad.

But how much should we mourn for a company that every year churned out thousands of tons of a substance doctors say is bad for us? How many tears should we shed for a plantation that for well over a century ran Maui like a gigantic factory, depleting the island’s soil, diverting its streams and filling its skies with smoke?

Maui Mayor Alan Arakawa called A&B’s announcement “the end of an era,” but is it even truly that?

*

Michigan Technological University anthropologist Carol MacLennan has studied every one of Hawaii’s sugar mill closures, dating back to the late 1960s. Her 2014 book Sovereign Sugar: Industry and Environment in Hawai‘i (published by University of Hawaii Press) is a sweeping look at the tremendous ecological changes sugar brought to the state.

“[A closure] can be traumatic,” she told me by phone. “Most of the Big Five dwindled as they diversified their holdings. But A&B has this unusual power on Maui. Because A&B has such a local identity, there’s an assumption of loyalty.”

Sugar production spans 150 or so years of Hawaii history, but it’s greatest years stretched from 1840 (when the Hawaiian kingdom reigned supreme) to 1940 (when the Territory of Hawaii was converting into a massive military bastion for the U.S). In that century, sugar plantations had transformed the islands in ways so deep that they’ll be with us forever.

“By 1920, sugar had remolded the islands into a production machine that drew extensively on island soils, forests, waters, and its island residents, to satisfy North America’s sugar craving,” MacLennan wrote in Sovereign Sugar. “Native communities–human, plant, and animal–adapted, disappeared or found niches in which to survive on a small scale. Imported and transplanted peoples, plants, and animals largely replaced them.”

The plantations were sprawling–covering a quarter-million acres by 1920–and required thousands of workers. Because diseases introduced by contact with Europeans in the late 1700s had devastated Native Hawaiians (their numbers dropping from between 279,000-800,000 in 1780 to a mere 30,000 by 1900), the plantations imported huge numbers of workers of Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Puerto Rican and Portuguese workers, forming the “mixed plate” ethnic makeup that largely populates Hawaii today.

Such massive change occurred throughout Hawaii’s ecology. Thirsty sugar depleted the soil of nutrients and demanded huge quantities of water through rainfall and irrigation, according to MacLennan. The plantations also harvest whole forests for planting and fuel (though quickly learned that preservation also served a vital role).

In an attempt to control rats, plantation owners imported the mongoose in the 1880s. It “proved environmentally unsound,” according to MacLennan, and led to the wholescale slaughter of Hawaii’s ground-nesting birds.

By the the late 1880s, the plantation owners–who were intertwined with the missionaries who’d grown so powerful after the destruction of the old kapu system in the early 1800s–had grown so powerful that they forced the notorious Bayonet Constitution on King Kalakaua. Its mandate that only property owners could vote meant that two/thirds of Native Hawaiians no longer had a voice over the governing of their islands.

That, thankfully, is in the past. But sugar’s ecological influences over Hawaii are still here, will likely always be here.

“The resulting erasure of what remained of the Hawaiian landscape by sugar’s class of businessmen has serious consequences for sustainability in the islands,” MacLennan wrote. “The faith in the human power to manipulate nature and re-create new landscapes of production continues environmental change and, when not checked, degradation.”

This is why MacLennan told me that sugar will still exist on Maui “in ghost form.” “Sugar production is ceasing, but A&B is still there,” she said. “You still have a major company with say over the acreage.”

*

One group that certainly isn’t looking at the demise of sugar harvesting on Maui in romantic terms is the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation. Founded in 1974, the NHLC is a nonprofit public interest law firm that’s spent the last decade and a half petitioning the state–on behalf of the East Maui residents who make up Na Moku ‘Aupuni o Ko‘olau Hui–to restore flows in 27 Maui streams diverted by East Maui Irrigation (a subsidiary of A&B) to Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar (another subsidiary of A&B). It’s a tedious legal process, given that HC&S uses so much water that it’s long been loathe to give up.

In a March 2015 hearing, NHLC attorney Alan Murakami gave a pretty good reason why: They’re paying the State of Hawaii $160,000 a year for the rights to the streams, but receive 164 million gallons per day from them, according to a Mar. 22, 2015 Maui News article. Murakami noted that that comes out to less than a penny per 1,000 gallons of water–a helluva deal, considering that county water rates can be in excess of 75 cents per 1,000 gallons.

Historically, plantation owners like A&B have typically retained their water rights when they close mills, MacLennan told me. But it’s unclear how the mill’s closure will affect NHLC’s fight, since A&B has said it still wants some agricultural uses on its land.

Murakami didn’t return a phone call for this story, but he told Civil Beat on Jan. 6 that A&B’s decision to stop growing sugar will certainly impact the case. “The question is how much,” he said. “There’s clearly nothing more thirsty than sugar cane.”

Earthjustice attorney Isaac Moriwake, an attorney agreed. In 2014, Earthjustice helped bring about a settlement agreement with HC&S and Wailuku Water Co. on behalf of Hui O Na Wai Eha and Maui Tomorrow to restore the Waihee, Waiehu, Waikapu and Iao Streams.

“Bottom line, it’s a game-changer,” Moriwake told me. Because sugar requires so much more water than diversified agriculture, Moriwake said that even if A&B keeps all of HC&S’ 36,000 acres in ag, they’ll still require far less water than they do so now. “Now that HC&S is closing, we need to reset the fundamental assumptions,” he said. “If you don’t have a use, then the water needs to stay in the rivers and streams right now.”

What will also stop are the cane burns. The method of harvesting sugar by burning the cane in the fields–the subject of considerable controversy and the first ever lawsuit in Hawaii’s new Environmental Court–will cease by the end of 2016.

The mill itself could be pretty dirty as well. In 2014, the state Department of Health slapped a $1.3 million fine on HC&S for 400 (!) air quality and reporting violations at the mill from 2009 to 2013. HC&S is still in discussions with the DOH over the fine and violations.

The plantation could also be an extremely dusty place. In our Nov. 29, 2015 issue, we explored one fugitive dust complaint in depth–one that led to a $3,300 violation against HC&S. Workers were working on a windy day in December 2014 over by the Maui Humane Society, and the dust cloud they kicked up caused one resident to complain.

That Central and South Maui could become even dustier once A&B stops growing sugar is a very real fear.

“I’ve read accounts from the 1800s of dust clouds hundreds of feet high and sandstorms so thick a rider could not see the ears on her own horse,” historian Jill Engledow posted on herMaui Then and Now blog on Jan. 6. “I live downwind, and I’d rather have occasional cane smoke.”

For their part, A&B officials insist that they will take steps to keep Central Maui from becoming even more of a dust bowl.

“As the lands are harvested, they will be replanted in a cover crop, transitioned to a replacement crop, or be allowed to return to their natural state with native ground cover,” A&B spokesperson Tran Chinery told me.

The use of the term “native ground cover” is ironic, given how much of Maui’s native ground cover vanished when the sugar plantation came in.

*

A huge array of questions remain over the future of the HC&S plantation. Will A&B sell off some or all of that land to homebuilders? Will the “task force” recently set up by the Arakawa Administration help laid off HC&S workers find new work? Will Monsanto sweep up more land? Both are too early to say. But another question could be problematic: what will become of the power-sharing agreement between HC&S and Maui Electric Co. (MECO) once the mill shuts down?

“The amount of power we currently receive from HC&S is a small percentage and since October of last year, HC&S has not exported any power to Maui Electric,” MECO spokesperson Kaui Awai-Dickson told me (their agreement stipulates that the mill provide MECO four megawatts of power from March to May and October to December).

That’s good, but there’s a snag. “However, over the years, HC&S has provided reserve or backup power that was available almost immediately to support Maui’s electrical system during extenuating circumstances,” Awai-Dickson added. “Such examples include severe storms or hurricanes where electrical infrastructure is severely damaged or a large generator is lost. Under these conditions, Maui Electric may not have a sufficient amount of reserve capacity to serve all customers at times when the demand for electricity is high. We are exploring possible options to replace this generation support including Demand Response programs, distributed generation, additional utility scale generation, and emergency generators.”

Throughout Hawaii, former sugar lands have given way to a variety of uses–homes, resorts, mac nut fields. It’s likely some or all of that will end up here, though it’ll be some time before we know for certain. In 1971, according to Sovereign Sugar, the Kohala Sugar Co. on the Big Island announced that it would close, putting 500 people out of work. Transition there was rough and took seven years.

On Jan. 6, A&B released some details about three “diversified agriculture” test projects they intend to implement on their 36,000 acres:

• Energy crops: “HC&S has initiated crop trials to evaluate potential sources of feedstock for anaerobic conversion to biogas,” stated the company’s press release. The statement added that HC&S has entered into “preliminary, but confidential, discussions with other bioenergy industry players to explore additional crop-to-energy opportunities.”

• Cattle: As noted above, HC&S is “working with Maui Cattle Company to conduct a grass-finishing pasture trial in 2016.”

• Food crops: “A&B plans to establish an agriculture park on former sugar lands in order to provide opportunities for farmers to access these agricultural lands and support the cultivation of food crops on Maui.” Former company employees would get preference in leasing lots.

“A&B is committed to looking for optimal productive agricultural uses for the HC&S lands,” A&B President and CEO Christopher J. Benjamin said in his company’s Jan. 6 announcement. “Community engagement, resources stewardship, food sustainability and renewable energy are all being considered as we define the new business model for the plantation. These are leading us toward a more diversified mix of operations.”

While all this sounds great to most residents, they also struck anthropologist MacLennan as very familiar. “It’s seen as a good thing to get away from monocrop production,” she told me. “People expect that these will keep wages up, but they’re always experimental. Diversified agriculture has been proposed since the 1920s, ‘30s. There’s a long history of it in my research, but it doesn’t always succeed.”

Cover photo: Tamara McKay

Leave a Reply